The Road to Independence: Forging a New Identity

The post-war political awakening, self-governance, and the birth of a nation.

The Singapore that emerged from Japanese occupation was fundamentally different from the compliant colonial city that had fallen in 1942. The war had shattered old certainties and awakened new possibilities. In the ruins of British prestige, a generation of leaders arose who would transform Singapore from colonial outpost to sovereign nation in just two decades.

The Political Awakening

The post-war years brought unprecedented political ferment. Students, trade unionists, and intellectuals who had witnessed colonial vulnerability during the war began demanding genuine self-governance. The old colonial compact—prosperity in exchange for political passivity—no longer satisfied a population that had learned survival required taking control of their own destiny.

The British, recognizing the changed mood, began gradual constitutional reforms. The 1955 Rendel Constitution granted Singapore limited self-government, with elected members forming a majority in the Legislative Assembly for the first time. The subsequent elections became a contest between different visions of Singapore's future.

Into this political arena stepped the People's Action Party (PAP), founded in 1954 by a group of English-educated professionals led by a brilliant young lawyer named Lee Kuan Yew. The PAP's appeal lay in its promise to bridge Singapore's communities while pursuing genuine independence, not mere autonomy under continued British oversight.

The Rise of Lee Kuan Yew

The 1959 elections marked Singapore's political coming of age. The PAP won a stunning victory, capturing 43 of 51 seats, and Lee Kuan Yew became Singapore's first Prime Minister at age 35. His victory speech was prophetic: "We are going to have a multiracial nation in Singapore. This is not a Malay nation, this is not a Chinese nation, this is not an Indian nation. Everybody will have his place."

Lee's government moved swiftly to establish Singapore's credibility as a modern state. They launched massive public housing programs, expanded education, attracted foreign investment, and most crucially, began building the institutional foundations that would outlast any single leader. The civil service was professionalized, corruption was ruthlessly suppressed, and economic planning replaced the laissez-faire approach of colonial rule.

Yet full independence seemed impossible for a small island with no natural resources beyond its strategic location. Singapore's leaders believed their future lay in union with the larger Malayan peninsula, where shared history and economic complementarity could create a viable nation.

The Malaysian Dream

The opportunity came when Malayan Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman proposed forming Malaysia, combining Malaya, Singapore, and the British Borneo territories. For Lee Kuan Yew, merger represented Singapore's path to meaningful independence within a larger, economically viable federation.

On September 16, 1963, Singapore joined Malaysia amid great celebration. The new federation seemed to offer the best of both worlds—Singapore would contribute its commercial expertise while gaining access to Malayan markets and resources. The island's Chinese-majority population would be balanced within a larger Malay-majority nation, creating space for all communities.

The honeymoon was brief. Fundamental disagreements over economic policy, racial integration, and federal power quickly surfaced. Singapore's leaders advocated a "Malaysian Malaysia" where merit, not ethnicity, determined opportunity. Malayan leaders viewed this as a threat to Malay political primacy and the delicate racial balance that had emerged since independence.

The Painful Separation

Political tensions escalated into racial violence. The 1964 race riots in Singapore exposed the deep fissures within the Malaysian experiment. PAP attempts to contest elections in mainland Malaysia were seen as Chinese chauvinism, while federal attempts to diminish Singapore's autonomy were viewed as Malay dominance.

By 1965, the situation had become untenable. Behind closed doors, Malaysian and Singaporean leaders reluctantly concluded that separation was inevitable. On August 7, 1965, the Malaysian Parliament voted to expel Singapore from the federation.

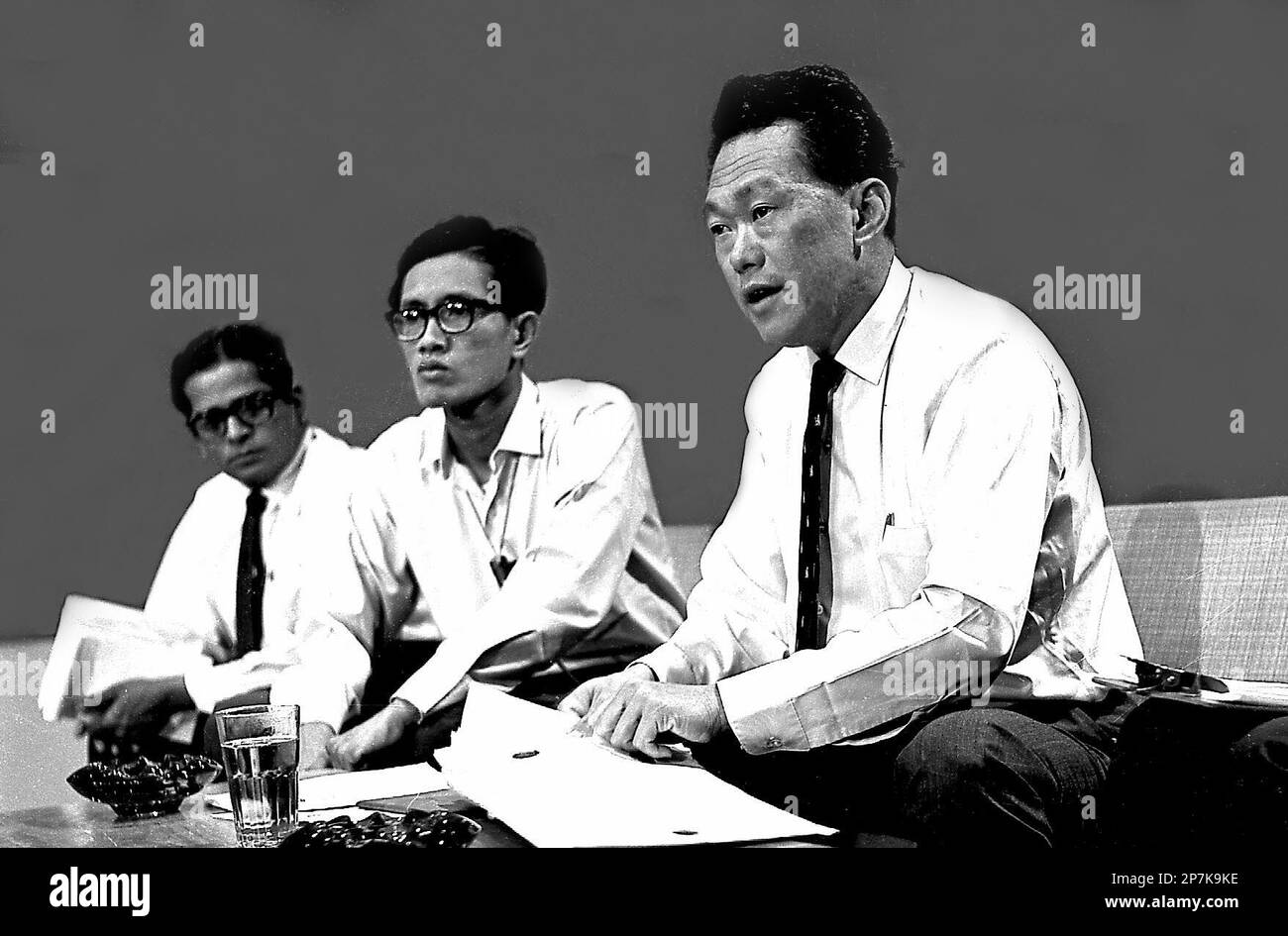

Two days later, on August 9, 1965, Lee Kuan Yew announced Singapore's independence to a stunned nation. The televised press conference became one of the defining moments in Singapore's history—the normally composed Prime Minister breaking down in tears as he described the "moment of anguish" when "a people die."

Birth of a Nation

Singapore's independence was not won through revolution or negotiation, but thrust upon a reluctant leadership who had wanted union, not separation. The new nation faced daunting challenges: no natural resources, potential enemies on all sides, a tiny domestic market, and deep uncertainties about economic survival.

Yet August 9, 1965, also marked a moment of liberation. Singapore was finally free to pursue its own destiny, unencumbered by the racial politics and economic constraints that had made the Malaysian experiment impossible. The small island that had once been great, then colonized, then occupied, then federated, was finally master of its own fate.

The tears of that independence day would soon give way to the determined effort to build something unprecedented—a successful city-state in the modern world.