The British Colonial Era: Founding a Modern Port

From Sir Stamford Raffles' arrival in 1819 to the growth of a bustling global trading hub.

On January 29, 1819, a lone British ship anchored off the sleepy island that had once been the mighty Singapura. Aboard was Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, a visionary administrator who saw in Singapore's forgotten harbors the makings of an empire's crown jewel. In a single stroke of diplomatic genius, he would transform this backwater into one of history's most successful cities.

The Fateful Landing

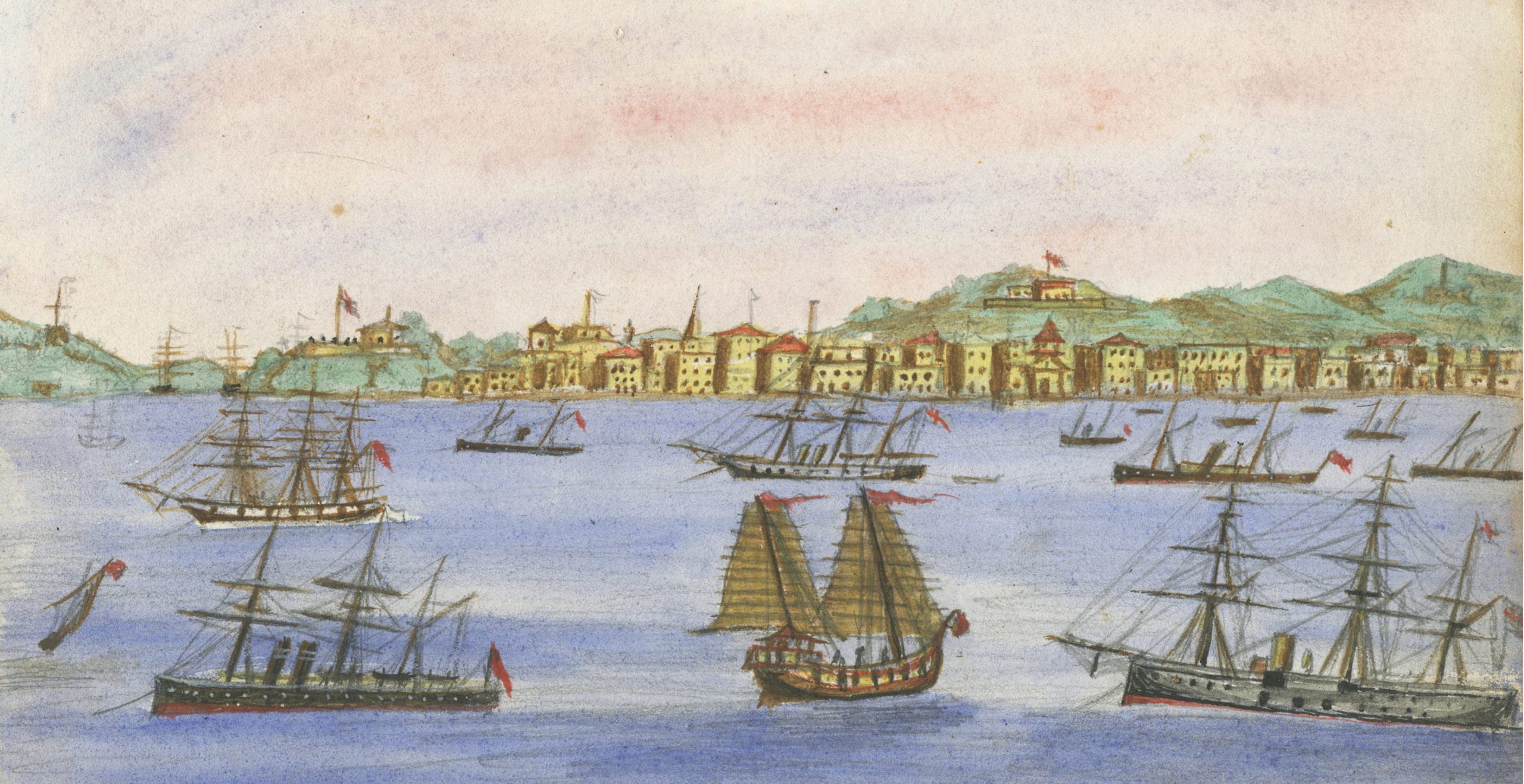

Raffles arrived with a clear mission: secure a strategic foothold for British trade in the vital sea lanes between India and China. The Dutch controlled most regional ports, but Singapore remained unclaimed—technically under the Johor Sultanate, but practically abandoned. Here was opportunity disguised as obscurity.

The situation Raffles encountered was delicate. Two claimants disputed the Johor throne, and the Dutch maintained they controlled regional waters. With characteristic boldness, Raffles recognized Hussein Shah as the rightful Sultan and negotiated a treaty on February 6, 1819. In exchange for annual payments, Britain gained the right to establish a trading post on Singapore island.

The treaty's ink was barely dry before Raffles began implementing his revolutionary vision: Singapore would be a free port, open to all nations and all traders, with no tariffs or restrictions on commerce. This radical departure from the protectionist policies of the era would prove to be the masterstroke that ensured Singapore's meteoric rise.

The Free Port Miracle

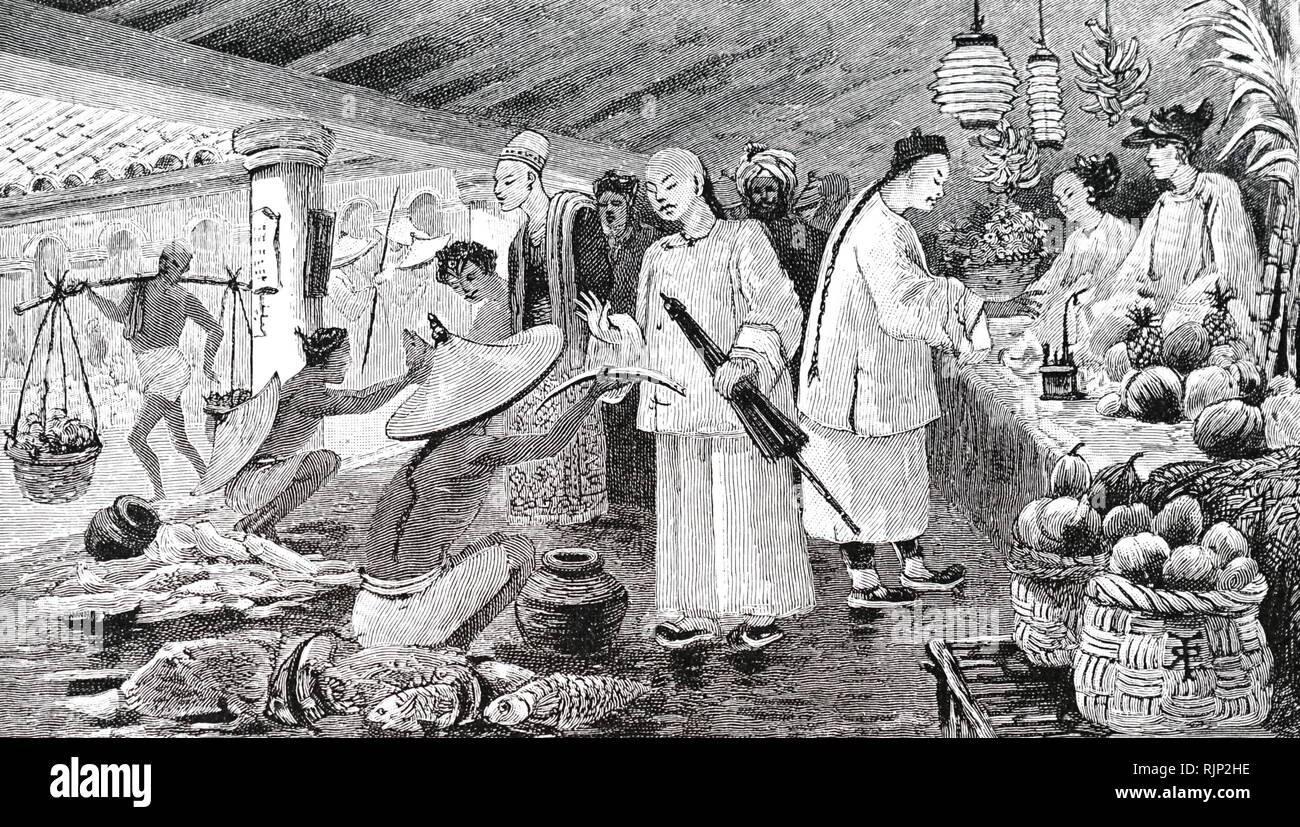

The results were immediate and spectacular. Within months, merchants from across Asia flocked to this new entrepôt where goods could be traded freely without the crushing taxes and bureaucratic restrictions that plagued other ports. Chinese junks arrived from Canton loaded with tea and silk. Arab dhows brought precious spices from the Indies. British steamers carried manufactured goods from the industrial heartland.

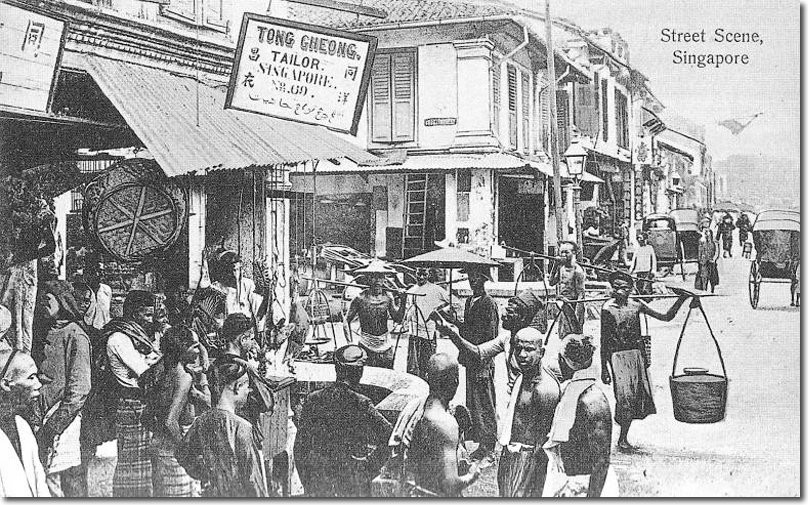

By 1821, Singapore's trade volume had exploded to over eight million Spanish dollars annually. The island's population, barely 1,000 when Raffles arrived, swelled to over 10,000 within three years. Malay fishermen were joined by Chinese merchants, Indian laborers, Arab traders, and European administrators in a cosmopolitan mix that would define Singapore's character for generations.

This wasn't mere commercial success—it was urban alchemy. Raffles had discovered that in the interconnected world of maritime Asia, a truly free port could capture trade flows like a magnet, drawing commerce away from heavily regulated competitors.

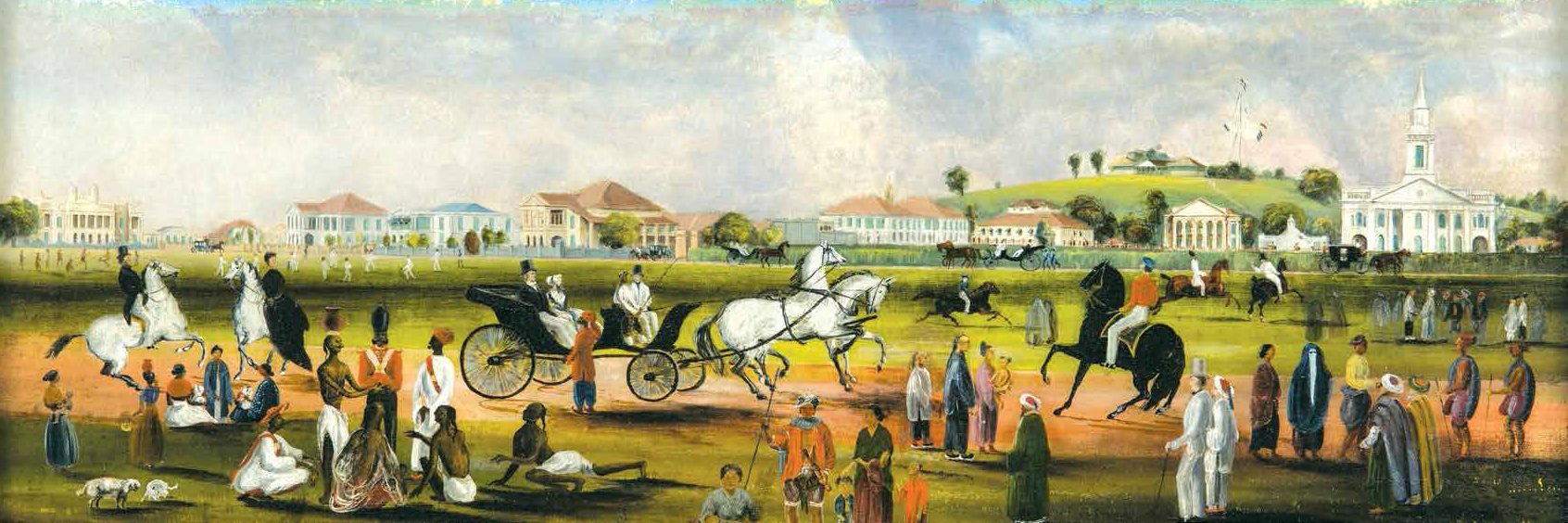

Designing a City

Recognizing that rapid growth required careful planning, Raffles developed his famous Town Plan in 1822. This wasn't merely urban design; it was social engineering on a grand scale. The plan allocated specific districts to different communities: Chinese merchants clustered around the Singapore River, Indian traders settled in Chulia Street, Arabs established themselves in Kampong Glam, while Europeans commanded the civic center around Fort Canning.

These ethnic quarters weren't segregationist walls but practical accommodations to cultural preferences and commercial networks. Chinese traders wanted proximity to their clan associations and temples. Muslim merchants needed access to mosques and halal food. Each community could maintain its traditions while participating in the larger commercial symphony.

The Town Plan's genius lay in its recognition that diversity was Singapore's strength, not its weakness. By providing space for different communities to flourish, Raffles created a city that could tap into trade networks spanning from the Middle East to China—a cosmopolitan advantage no homogeneous settlement could match.

The Imperial Nexus

Within decades, Singapore had become the indispensable hub of British imperial commerce in Asia. Raw materials from Malaya's tin mines and rubber plantations flowed through its warehouses. Manufactured goods from British factories found Asian markets via Singapore's traders. The city's banks financed regional development while its shipping lines connected distant colonies.

Yet Singapore was never merely a British outpost. Its success depended on embracing the region's diversity, languages, and traditions. This delicate balance between imperial purpose and local adaptation would shape Singapore's unique identity as it grew from Raffles' bold gamble into the thriving heart of British Southeast Asia.